Frank Draper

| Date and Place of Birth: | September 16, 1918 Bedford, VA |

| Date and Place of Death: | June 6, 1944 off the coast of Normandy, France |

| Baseball Experience: | Semi-Pro |

| Position: | Outfield |

| Rank: | Technical Sergeant |

| Military Unit: | 1st Battalion, Company A, 116th Infantry Regiment, 29th Infantry Division US Army |

| Area Served: | European Theater of Operations |

Frank Draper could hit, run and field with the best of them. He also became a fine soldier. Frank Draper was one of the Bedford Boys.

Frank P. Draper, Jr., the son of Frank and Mary Draper, was born in Bedford, Virginia on September 16,

1918. Times were hard for the Draper family but the boys - Frank, David

and Warren - had baseball to keep them busy. "When we were growing up in

Bedford," recalls David Draper, "There wasn't much going on here for

young people, so from a young age [Frank] was always playing sports in

and around Bedford. That's how he became such a good athlete." [1]

Frank played baseball for Mud Alley - a tough neighborhood team and

starred with Bedford High School in baseball, football, basketball and

track. Later on, he became the center fielder and lead-off hitter with

the semi-pro Hampton Looms team, the areas largest employer. Batting two

and three for the team were his brothers. [2]

Draper, like many of the local youngsters, was also a member of the

local National Guard - enticed by the promise of a dollar every Monday

night after marching practice at the Bedford Armory. [3]

As the war in Europe took hold in 1940, the United States began to

expand its fighting forces. In October, it was announced that Bedford's

National Guard Company A would be mobilized into the federal Army for a

period of one year.

Four months later, on February 3, 1941, Draper and the other members of

Company A reported to the Bedford Armory where they were issued new

uniforms and sworn in. They were sent to Fort Meade, Maryland, home of

the 29th Infantry Division where they were taught to be soldiers.

It was while returning to Fort Meade from military exercises in North

Carolina that news of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor reached Draper

and the boys of Company A. It ended all hope of being home in a year -

Draper was now in the Army for the duration. But the Army proved to be

the making of Frank Draper. He was resourceful, calm and decisive under

pressure. He kept a diary detailing his duties and responsibilities and

quickly attained the rank of sergeant. [4]

In August 1942, the 29th Infantry Division left Fort Meade bound for

Camp Blanding in Florida. Less than a month later they were preparing to

move out although they had no idea where they were going - the Pacific

or Europe. "The last time we saw Frank was September 1942," recalls his

sister Verona Lipford. "My mother, Frank's girlfriend and I, went to

Camp Blanding to see him before he shipped out. He left our motel that

evening as jovial as always." [5]

The 29th boarded a train that took them to Camp Kilmer, New Jersey -

staging post to Britain. A total of 11,000 troops boarded the Queen Mary

for the Atlantic crossing with an escort of five destroyers and a

British cruiser, HMS Curacoa. As the Queen Mary approached Scotland it

was the Curacoa that guided her to the Forth of Clyde. It was a routine

operation but at 2.12pm on October 2, 1942, disaster struck. The Queen

Mary collided with the Curacoa. The Queen Mary suffered minimal damage

but the Curacoa sank almost immediately from the impact of the huge

ocean liner and 338 lives were lost. [6]

Shaken, but safely on dry land in Scotland, the 29th moved by train to

London and from there to Tidworth Barracks just ten miles from

Stonehenge. The 29th had begun their training program in October 1942

and it would last until May 1944 - the longest of any US infantrymen in

World War II. [7]

But Draper still found a little time for baseball. In September 1943, he

played for the 116th Infantry Regiment Yankees in a four-day tournament

in London. The 116th were a darkhorse team at the outset - unknown to

many of the other teams who were playing in well-established military

leagues around Great Britain. Draper, together with Bedford boys

Elmer

Wright and Tony Marsico, were the backbone of the team and Draper

collected three hits, including two triples in the 6-3 final against 8th

Air Force Fighter Command that saw the 116th Infantry Regiment Yankees

crowned ETO champions. [8]

That was to be Draper's last chance to play baseball. For the remainder

of 1943 and the first five months of 1944 it was intensive military

training in preparation for the invasion of mainland Europe.

But like most servicemen overseas, Draper's thoughts were often on the

things he missed back home, as can be clearly derived from the poem he

sent home:

Old Friends and New

I'm sitting here just thinking,

Of things I left behind.

A girl with brown eyes gleaming,

Of Mother so good and kind.

We miss our Mother's tender care,

We miss Her apple pie,

She's the best one of them all we swear,

And we couldn't tell a lie.

Nothing compares to a loving mother,

To her kindness and concern,

Once she's gone, there is no other,

For her we'll always learn.

When all the world is bright once more,

And full of smiling faces,

We can all go back to the old home shore,

Back to familiar places.

When all this strife is over,

After the peace is signed,

We'll forget the planes o'er Dover,

Forget the Nazi whine.

These humble lines I pen to her,

While far across the sea,

Wishing that I'd never stir,

From the land that's home to me.

So again your loving boy will say,

There's none so good and kind,

We'll meet again some happy day,

far across the Ocean's brine.

To Mother

by Sgt. Frank P Draper [9]

On the morning of June 6, 1944, Technical Sergeant Frank Draper was on a

landing craft heading for Omaha Beach at Normandy. Company A of the

116th Infantry Regiment were to lead the assault on D-Day.

As the landing crafts approached the beach the enemy opened fire.

Draper's craft shook with the impact of an anti-personnel shell that

tore off his upper arm as he stood in the middle of the craft. Rapidly

losing blood, the young soldier slumped to the floor. [10] The

fleet-footed outfielder from Bedford, Virginia was dead.

It was not until July 16 that news of the horrendous losses suffered by

Company A reached the tight knit Bedford community. Nineteen Bedford

boys died in the first bloody minutes of D-day. Two more died later in

the day. No other town in America suffered a greater loss. [11]

To mark Frank Draper's 26th birthday on September 16, 1944, his mother

sent a memorial letter to the local newspaper:

I can't even see your grave except in a dream. Now my mind wanders

thousands of miles across the mighty deep. To a lonely little mound in a

foreign land where the body of my dear soldier boy might be lain away.

This tired, homesick soldier boy who attended church in Bedford all his

life. He was not buried in a nice casket, flowers and funeral

procession. His dear body was laid to rest in a blood-soaked uniform.

Maybe it was draped in an American flag. There will not be any more

cruel wars where you have gone, dear Frank...The old rugged cross has a

two-folded meaning for me, for my own dear boy shed his precious blood

like Jesus on the cross at Calvary. For our religious freedom, they say.

A dear price to pay. [12]

In 1947, Frank Draper's body was returned to Bedford and now rests at

Greenwood Cemetery.

On June 6, 1954, ten years after the tragic losses at Normandy, a

memorial to the Bedford boys was unveiled in the town. On June 6, 2001,

the national D-Day Memorial was opened in Bedford.

Frank Draper (far right) in London with Elmer Wright, Robert Marsico and Pride Wingfield

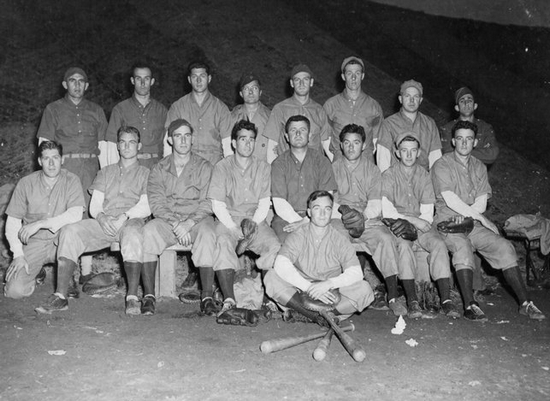

116th Infantry Regiment Yankees (Frank Draper is back row, second left)

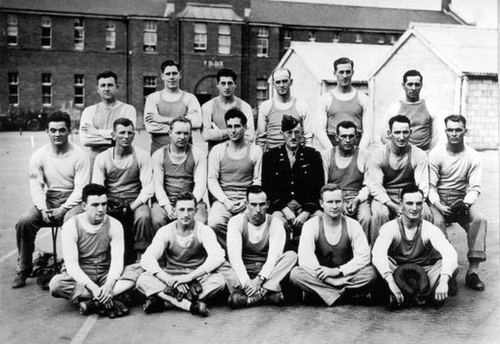

116th Infantry Regiment Yankees in England (Frank Draper is middle row, far right)

116th Infantry Regiment Yankees after winning the

1943 ETO championship

Frank Draper is in the front row, second from left

Frank Draper's grave at Greenwood Cemetery in Bedford, Virginia

A memorial to Frank Draper, Jr., at Greenwood Cemetery in Bedford, Virginia

Notes

1 Correspondence, David Draper 1996

2 Bedford Boys, Alex Kershaw (DaCapo Press 2003)

3 ibid

4 ibid

5 Correspondence, Verona Lipford 1997

6 Bedford Boys

7 ibid

8 Stars and Stripes, October 1, 1943

9 unidentified press clipping

10 Bedford Boys

11 ibid

12 ibid

Date Added June 4, 2012 Updated May 16, 2017

Baseball's Greatest Sacrifice is associated with Baseball Almanac

Baseball's Greatest Sacrifice is proud to be sponsored by