Elmer Wright

| Date and Place of Birth: | October 11, 1915 Bedford, VA |

| Date and Place of Death: | June 6, 1944 Omaha Beach, Normandy, France |

| Baseball Experience: | Minor League |

| Position: | Pitcher |

| Rank: | Staff Sergeant |

| Military Unit: | Company A, 116th Infantry Regiment, 29th Infantry Division US Army |

| Area Served: | European Theater of Operations |

Elmer Wright was a great minor league pitcher who swapped his flannels for military fatigues. He trained for 22 months to be an infantryman. He survived only a few minutes in combat.

During the Great Depression, Bedford, Virginia, was a tight knit

community of about 3,000, and Elmere P. "Elmer" Wright was the son of

the town's deputy sheriff, Howard P. Wright. Elmer was a standout

athlete at Bedford High School, a tackle in football and a hard throwing

pitcher on the baseball team. After graduating from high school, the

funloving right-hander pitched for a number of local semi-pro teams and,

like many youngsters, he also joined Company A of the local National

Guard, if for no other reason than it paid a couple of dollars at a time

when money was hard to come by.

In the spring of 1937, Wright, age 21, attended the Ray L. Doan baseball

school at Hot Springs, Arkansas. From there he was signed by the St.

Louis Browns and assigned to the Terre Haute Tots of the Class B Three-I

League. He struck out 90 batters in the 74 innings he threw for the Tots

but could not win a game. After running his won-loss record to 0-7, he

was assigned to the Mayfield Clothiers of the Class D Kitty League,

where he was 7-7 with a 3.65 ERA and struck out 122 in 116 innings.

Wright pitched the last three innings of the Kitty League all-star game

in July (a 5-2 win over the Jackson Generals), and helped the Clothiers

to a fourth-place tie with Jackson. They then defeated Jackson in a

one-game playoff to secure fourth place and a playoff berth. The

Clothiers went on to defeat Union City in three games and take the

playoff title in five games over the Fulton Eagles.

Wright was with the Johnstown Johnnies of the Class C Middle-Atlantic

League for 1938. He made 30 appearances for a 6-14 record and two of

those victories occurred on the same day. He beat Dayton, 4-1, in the

opening game of a June 30 doubleheader, then pitched the first four

innings of the second game to take the victory in an 11-3 win. Wright

had shown enough to be called to the Class Al Texas League San Antonio

Missions' spring training camp in Brownsville, Texas, for 1939, but was

assigned to the Jackson Senators of the Class B Southeastern League for

the regular season, where he pitched 32 games for a 7-11 record and 5.45

ERA. He was back with the Missions for spring training in 1940, but was

a late cut, being sent to Meridian of the Class B Southeastern League.

However, Wright did not report and sat out the season.

As the war in Europe took hold during 1940, the United States began to

expand its fighting forces. In October, it was announced that Bedford's

National Guard Company A would be mobilized into the federal Army for a

period of one year, and on February 3, 1941, Wright and the other

members of Company A reported to the Bedford Armory. They were sent to

Fort Meade, Maryland, home of the 29th Infantry Division, and during the

summer of 1941, Wright regularly had the opportunity to pitch for the

Fort Meade post team. While at Fort Meade, news was received of the

Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. It ended all hope of being home in a

year.

In August 1942, Company A, as part of the 116th Infantry Regiment, 29th

Infantry Division, left Fort Meade bound for Camp Blanding in Florida.

Less than a month later they boarded a train that took them to Camp

Kilmer, New Jersey, staging post to Britain. A staggering total of

11,000 troops boarded the Queen Mary for the Atlantic crossing with an

escort of five destroyers and a British cruiser, HMS Curacao. As the

Queen Mary approached Scotland, the Curacao guided her to the Forth of

Clyde. It was a routine operation but at 12:12 P.M. on October 2, 1942,

disaster struck. The Queen Mary collided with the Curacao. The huge

ocean liner suffered minimal damage but the Curacao sank almost

immediately and the lives of 338 British sailors were lost.

Shaken, but safely on dry land in Scotland, the division moved by train

to London, England, and from there to Tidworth Barracks just ten miles

from historic Stonehenge. It was the beginning of the division's

training program that would last until May 1944, the longest of any

American infantrymen in World War II. Elmer Wright still found a little

time for baseball in England. In September 1943, he played for the 116th

Infantry Regiment Yankees in a four-day U.S. services baseball

tournament in London. The Yankees were a dark horse team at the outset

of the tournament - unknown to most of the other teams who were already

playing in well-established military leagues around Britain. Wright,

together with outfielder Frank Draper and catcher Tony Marsico (who were

also from Bedford, Virginia) were the backbone of the team. Draper had

grown up desperately poor on the wrong side of the tracks in Bedford. A

superb, naturally-gifted athlete, he had been the lead-off hitter with

the semi-pro Hampton Looms mill team before military service. Marsico

was 34 years old and a talented catcher who had played for the Piedmont

Label team. [1] Wright's pitching guided the Yankees to an unexpected

place in the final against Eighth Air Force Fighter Command. He started

the game for the Yankees and yielded four hits and a run over four

innings before giving way to former Penn State Association pitcher Doug

Gillette. The Yankees won the game, 6-3, for the European Theater

championship title (Draper had three hits that day, including two

triples). That was to be Wright's last chance to play any form of

competitive baseball. For the remainder of 1943 and the first five

months of 1944, it was intensive military training in preparation for

the invasion of mainland Europe.

Professional baseball back home had not forgotten about Elmer Wright,

however. In June 1943, he received an unexpected letter from the Toledo

Mud Hens, the club to whom he had been assigned shortly before entering

military service. "I just wanted to write you this note," penned Mud

Hens president G. E. Gilliland, "and let you know that I am mighty proud

of the fact that you are serving our country and to wish you the best of

luck. You boys over there are certainly doing a grand job.... After

throwing hand grenades at those Japs and Germans, your control should be

perfect and that is all that you ever needed to win anywhere so hurry up

and get this thing over with and get back over here because I could use

a good pitcher right now." [2]

Wright also found time to keep in touch with his parent club. A reply

from Browns' vice-president, William O DeWitt, dated March 16, 1944,

read:

Dear Elmere:

We have your very interesting letter of recent date and assure you it

was a pleasure to hear from you and to know something about you.

You certainly have spent quite a long stretch in the Army and if the

newspaper stories are correct, perhaps you will get a chance to return

to this country in the not too distant future.

We are mighty glad that you played some baseball and that you won the

Championship. Your record was certainly impressive: In fact, by not

losing any your record was perfect. I am glad to know that your

curveball and your control are better, even though your fastball is not

as good as it used to be. I think you will be a much better pitcher and

I know you will be ready for some high class baseball when you get back.

The Browns and Toledo begin spring training together at Cape Girardeau,

Missouri on Monday, March 20, with the American League season opening on

April 18 and the American Association on April 19.

The envelope in which your letter was sent to us is different from any

other envelopes we have received from overseas. Can you tell us the

reason your outfit uses this kind of envelope, or is that a military

secret? Can you tell us where you are stationed?

Thanking you for your letter and with continued good wishes, we are,

Sincerely yours,

William O DeWitt

Vice-President [3]

On May 18, 1944, the 116th Infantry Regiment of the 29th Infantry

Division were taken in trucks to containment camps on the south-east

coast of England. The countdown to D-Day had begun and Wright's military

skills were soon to be tested. Movement outside the camps was strictly

forbidden as absolute secrecy regarding invasion details was essential

and it was a boring and anxious couple of weeks for the men of Company

A. "Whenever we had time, I put on a glove and [Elmer Wright] pitched to

me," recalls former college catcher, Hal Baumgarten in Alex Kershaw's

The Bedford Boys. "Wright was fast. I had to put a double sponge in the

glove." [4]

On the morning of June 6, 1944, Staff Sergeant Wright was on a

landing craft heading for Omaha Beach at Normandy. Company A of the

116th Infantry Regiment was to lead the D-Day assault. As the landing

crafts approached the beach the enemy opened fire with artillery,

mortar, machine-gun and small arms fire. Frank Draper, the outfielder

from Bedford, was on another landing craft. The Army had been the making

of the 25 year-old. He was resourceful, calm and decisive under

pressure, yet totally unprepared for what was about to happen. Draper's

craft violently shook with the horrifying impact of an anti-personnel

shell that ripped through the metal side and tore off his upper arm.

Rapidly losing blood, the young soldier slumped to the floor and died in

a pool of blood, seawater and vomit.

Wright's landing craft made it to the beach and as the ramp dropped the

men were met with a hail of enemy fire. Most were killed outright.

Others lay critically wounded, screaming for help. Those that could,

jumped in to the six-foot of water and desperately tried to make their

way to the beach. Wright was killed in the hail of gunfire almost as

soon as he hit the beach.

It was not until July 16 that news of the horrendous losses suffered

by Company A reached the townsfolk of Bedford. Nineteen local boys died

in the first bloody minutes at Normandy. Two more died later in the day.

No other town in America suffered a greater loss.

Elmer

Wright is buried at the Normandy American Cemetery at

Colleville-sur-Mer in France.

|

Year |

Team |

League |

Class |

G |

IP |

ER |

BB |

SO |

W |

L |

ERA |

| 1937 | Terre Haute | Three-I | B | 16 | 74 | - | 48 | 90 | 0 | 7 | - |

| 1937 | Mayfield | Kitty | D | 21 | 116 | 47 | 64 | 122 | 7 | 7 | 3.65 |

| 1938 | Johnstown | Mid-Atlantic | C | 30 | 120 | 80 | 74 | 83 | 6 | 14 | 6.00 |

| 1939 | Jackson | Southeastern | B | 32 | 165 | 100 | 101 | 89 | 7 | 11 | 5.45 |

| 1940 | Meridian | Southeastern | B | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

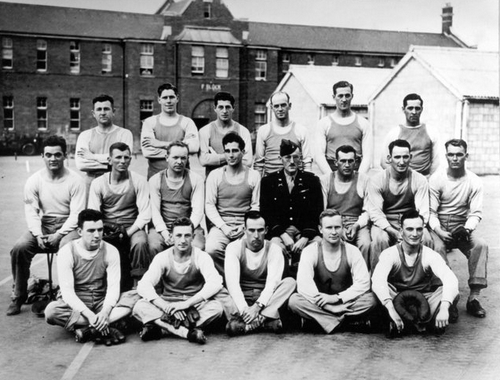

The 1937 Mayfield Clothiers.

(Elmer Wright is standing, third from left)

letter to Elmer Wright from G.E. Gilliland, president of the Toledo Mud Hens

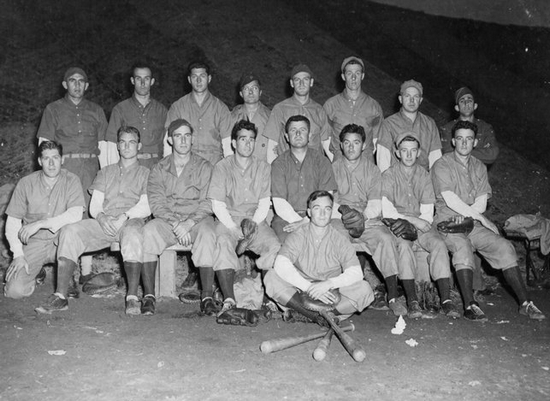

The 116th Infantry Regiment Yankees in England in

1943

(Elmer Wright is middle row, second from right)

The 116th Infantry Regiment Yankees in England in

1943 after winning the ETO World Series

(Elmer Wright is front row, third from left)

Elmer Wright (left) with Robert Marsico, Pride Wingfield and Frank Draper

Letter to Elmer Wright from William O. DeWitt, vice-president of the St. Louis Browns

The grave of Elmer Wright at the Normandy American Cemetery at Colleville-sur-Mer in France.

Notes

1. Catcher Robert Marsico suffered injuries to his right arm and leg

at Omaha Beach. He was hospitalized in England for three months and

spent the next year at a rehabilitation center in Norfolk, Virginia,

before being discharged in July 1945. Due to his injuries, Marsico's

ball-playing days were over. He returned to work with the Piedmont Label

Company, where he remained for 41 years and became an accomplished

golfer winning several club tournaments. Robert Marsico passed away in

August 1986, at the age of 77.

2. Letter from G. E. Gilliland, President, Toledo Baseball Company to

Sergeant Elmere P. Wright, dated June 7, 1943.

3. Letter from William O. DeWitt, Vice-President, St. Louis Browns to

Sergeant Elmere P. Wright, dated March 16, 1944.

4. Kershaw, Alex. The Bedford Boys: One American Town's Ultimate D-day

Sacrifice (DaCapo Press, 2004)

Date Added May 31, 2012 Updated June 13, 2014

Baseball's Greatest Sacrifice is associated with Baseball Almanac

Baseball's Greatest Sacrifice is proud to be sponsored by