Joe Pinder

| Date and Place of Birth: | June 6, 1912 McKees Rock, PA |

| Date and Place of Death: | June 6, 1944 Normandy, France |

| Baseball Experience: | Minor League |

| Position: | Pitcher |

| Rank: | Technician Fifth Grade |

| Military Unit: | HQ Company, 16th Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division, US Army |

| Area Served: | European Theater of Operations |

Medal of Honor recipient

"Almost immediately on hitting the waist-deep water, he was

hit by shrapnel. He was hit several times and the worst wound was to the

left side of his face, which was cut off and hanging by a piece of

flesh."

Second Lieutenant Lee Ward W. Stockwell

John J. “Joe” Pinder, Jr., a stocky right-hander, was born in McKees

Rocks, Pennsylvania, an industrial suburb of Pittsburgh along the west

bank of the Ohio River.

His father worked in the steel mills and the family moved around the

state wherever work could be found. By 1929, they were in Butler and Joe

graduated from Butler High School in 1931. Pinder then played sandlot

baseball until signing with the Butler Indians, a new entry in the Class

D Pennsylvania State Association in 1935. He made eight appearances for

the Indians for a 3–2 record and 3.33 ERA. In 1936, Butler became a

Yankees farm club and consequently changed its name to the Butler

Yankees. Pinder was released by the club in early May and pitched for

the semi-pro Sterling Oils of Emlenton, Pennsylvania.

In 1938, Pinder decided to give professional baseball another go and

successfully tried out for the Sanford Lookouts of the Class D Florida

State League, a Chicago White Sox affiliate. The Lookouts spent the

season in the basement and Pinder was the workhorse of the mound staff.

He finished the year with a 9–18 won-loss record and lost 10 games in a

row, but high points were a one-hitter against St. Augustine on June 30

and another against DeLand on July 29. “Pinder has a lot of stuff and

his curve ball is dreaded by the other clubs in the league,” declared

the Sanford Herald. “His fast ball comes in very handy after he slips a

curveball by and it hops and travels with more speed than one of an

average hurler. The youngster has the stamina and courage to make a big

leaguer some day and he takes his work very seriously.”

Pinder was back with the Lookouts in 1939, and with former American

League batting champion Dale Alexander as manager, he enjoyed the best

season of his career. As part of a starting rotation that included

future major leaguers Sid Hudson and Harry Dean, Pinder posted a 17–7

won-loss record and 3.92 ERA as the team cruised to the league title

(Hudson was 24–4, while Dean was 21–4). Pinder began his third year with

Sanford in 1940. The team had ended its affiliation with the White Sox

in 1939, and now operated independently changing its name to the

Seminoles, and on May 13, he left the club to join the Macon Peaches of

the South Atlantic League, a Class B circuit and the highest

classification he would play at. His time at Macon, however, was

short-lived as he returned to Florida and joined the Fort Pierce Bombers

of the Class D Florida East Coast League in June. The Bombers finished

221⁄2 games out of first place and Pinder had a 4–12 won-loss record

despite a 3.79 earned run average.

Pinder spent the winter months of 1940-1941 in Pennsylvania with his

parents and registered for the selective service while there, returning

to Fort Pierce for spring training.

“Joe Pinder, the stocky, square-set little Pennsylvanian with the

blinding fast ball,” wrote the Fort Pierce News-Tribune in February

1941, “is back in town and is ready for the ... 1941 baseball season.”

The Bombers were a better team in 1941, and Pinder was 11–9 with a 3.06

ERA when he was optioned in July to the Greenville Lions of the Class D

Alabama State League. He was 6–2 in 10 appearances with the Lions and

his ERA was a career-low 2.48. On August 18, he performed the unusual

task of starting both games of a doubleheader, throwing a shutout in the

opener and receiving a no-decision in the second game. On August 28,

1941, Pinder hurled what was to be his last professional game, a 7–1 win

over the Tallassee Indians.

Pinder entered military service on January 27, 1942; two days before his

younger brother, Harold, entered service with the Army Air Force. Joe

Pinder received basic training with the Army at Camp Wheeler, Georgia;

Fort Benning, Georgia; and Fort Indiantown Gap, Pennsylvania, before

leaving for England with the 16th Infantry Regiment, 1st “Big Red One”

Infantry Division. In November 1942, the division left England and took

part in the Allied landings of North Africa at Algeria and the battles

against Rommel’s Afrika landings on Gela in Sicily, and then slogged

through the island’s mountains where some of the heaviest fighting of

the Sicilian campaign took place.

By November 1943, Technician Fifth Grade Pinder was a one-year combat

veteran back in England preparing for D-Day, the Allied invasion at

Normandy. Meanwhile, brother Harold, now a first lieutenant and a bomber

pilot with the 44th Bomb Group which was also stationed in England, was

shot down on a raid over Europe on January 29, 1944. With the help of

the Belgian Resistance he managed to avoid capture until April when he

was rounded up by German troops and spent the remainder of the war at

Stalag Luft III.

On the morning of June 6, 1944, the 16th Infantry Regiment was in the

first wave of troops to assault the beaches at Colleville-Sur-Mer, more

commonly known as Omaha Beach. Joe Pinder was aboard a landing craft of

men from the regiment’s Headquarters Company. For Pinder it was a

special day—his birthday. He was 32.

As the landing crafts approached the beach the Germans opened fire with

artillery, mortars and machine-gun fire. An artillery shell exploded

close to Pinder’s landing craft, tearing holes in the boat and causing

carnage among the men inside. For those that survived, Pinder included,

panic set-in as the vessel filled with water and began to sink. Still

100 yards from the beach the ramp was dropped and they were instantly

met with a hail of deadly accurate machine-gun and small arms fire,

killing many outright as they struggled to reach the shore. As in

baseball, Pinder took his work very seriously, and despite the chaos, he

was determined to do what he was there for—to ensure vital radio

equipment made it to the beach so a line of communication could be

established. He grabbed a radio and placed it on his shoulder and amid

the deafening sound of gunfire, made his way down the ramp and into the

waves.

With the air filled with small arms fire and exploding artillery it was

only a matter of time before Pinder was hit. As he desperately waded

through the water, a bullet clipped him, causing him to stumble, but he

did not stop. Another bullet ripped through the left side of his face

and he held the gaping flesh in place as he carried on. Pinder made it

to the beach, dropped the radio and returned to the water to retrieve

more equipment. Then, instead of looking for somewhere to protect

himself from the relentless enemy barrage, he returned a third time to

collect essential spare parts and code books. Again he was hit as a

burst of machine gun fire tore through his upper body. He fell, then

somehow struggled to his feet, and with his last ounce of energy made it

to the beach and his radio equipment. Moments later he passed out from

loss of blood and died later that morning.

Joe Pinder had made the ultimate sacrifice in helping to establish vital

radio communication on Omaha Beach.

On January 4, 1945, Pinder was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor

for conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity above and beyond the call of

duty. The medal, the nation's highest award, was received by his father

from Major General Philip Hayes, commanding officer of the Third Service

Command. “The indomitable courage and personal bravery of T/5 Pinder,”

claimed his citation, “was a magnificent inspiration to the men with

whom he served.”

Pinder was originally buried at the U.S. military cemetery at St.

Laurent, Normandy, but his body was returned home

in September 1947, and now rests at Grandview Cemetery in Florence,

Pennsylvania, where a monument was erected in his honor in October 2000.

Fifty-five years after his death, fourteen members of Pinder's family

and many local dignitaries attended the ceremony.

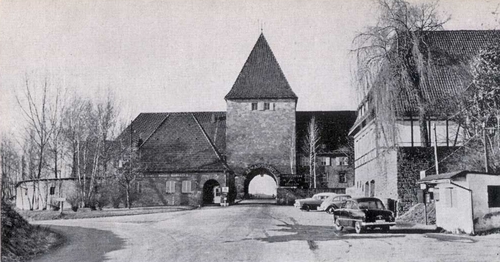

On May 11, 1949, the U.S. Army barracks at Zirndorf, Germany, was

renamed Pinder Barracks in his honor. Although the barracks have since

been torn down, a business park known as Pinder Park now occupies the

area.

A memorial for Pinder is also located in McKees Rock between Chartiers Creek and the entrance to the shopping center on Chartiers Avenue (Route 51).

In January 2014, the Pinder family gave his medals, citations and memorabilia to the Soldiers & Sailors Memorial Hall & Museum in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. An exhibit was created and opened on Memorial Day, May 26, 2014.

|

Year |

Team |

League |

Class |

G |

IP |

ER |

BB |

SO |

W |

L |

ERA |

| 1935 | Butler | Penn State Assoc | D | 8 | 46 | 17 | 29 | 35 | 3 | 2 | 3.33 |

| 1936 | Butler | Penn State Assoc | D | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 1937 | Played semi-pro baseball for Sterling Oils | ||||||||||

| 1938 | Sanford | Florida State | D | 43 | 234 | 105 | 155 | 156 | 9 | 18 | 4.04 |

| 1939 | Sanford | Florida State | D | 35 | 211 | 93 | 115 | 117 | 17 | 7 | 3.94 |

| 1940 | Sanford | Florida State | D | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 1940 | Macon | South Atlantic | B | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 1940 | Fort Pierce | Florida East Coast | D | 23 | 114 | 48 | 81 | 72 | 4 | 12 | 3.79 |

| 1941 | Fort Pierce | Florida East Coast | D | 27 | 168 | 64 | 94 | 102 | 11 | 9 | 3.06 |

| 1941 | Greenville | Alabama State | D | 10 | 58 | 16 | 31 | 34 | 6 | 2 | 2.48 |

Joe Pinder, back row, far left, with the Sanford Lookouts

Joe, on right, with his brother, Harold, during their last meeting in England in 1943

The U.S. Army's Pinder Barracks at Zirndorf, Germany (circa. 1950s)

Joe Pinder's burial at Grandview Cemetery in Florence, Pennsylvania, 1947

Memorial to Joe Pinder at Grandview Cemetery in Florence, Pennsylvania

Source

The Sacrifice for Freedom project website created by Emily Keating

http://johnjpinderjr.weebly.com/

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, June 5, 2014

Date Added February 6, 2012 Updated June 7, 2014

Baseball's Greatest Sacrifice is associated with Baseball Almanac

Baseball's Greatest Sacrifice is proud to be sponsored by