Nay Hernandez

| Date and Place of Birth: | October 12, 1919 San Diego, CA |

| Date and Place of Death: | March 22, 1945 Ludwigshafen, Germany |

| Baseball Experience: | Minor League |

| Position: | Outfield |

| Rank: | Private |

| Military Unit: | 376th Infantry Regiment, 94th Infantry Division US Army |

| Area Served: | European Theater of Operations |

Nay Hernandez was San Diego's opening day left fielder in his rookie season in 1944. At the end of the year he was in the Army. By the following spring he was dead.

Manuel P. “Nay” Hernandez came from a big family. He had ten sisters

and four brothers, and he and his twin sister, Margarita, were among the

youngest. His parents, Francisco and Gregoria, were originally from

Mexico and moved to San Diego in 1903, when Gregoria’s brother, who had

a job on the railroad in San Diego, paid a penny in immigration fees for

each of his sister’s family to enter the United States.

Francisco found work on farms in southern San Diego County before

working for the Street Department of the City of Chula Vista, but with

so many mouths to feed, the family was far from wealthy. However, they

had a roof over their heads and food on the table. They also had

baseball and the Hernandez children loved baseball. “Our whole family

played ball,” remembered Nay’s sister Valentina. “We had our own

Hernandez team and we’d play everybody. My sisters were good too, but

Nay was the best.”

Hernandez was passionate about the game. “All he wanted to do was play

baseball,” recalled Valentina. “Everyday after school he’d go practice.

My mother would ask where he was and Nay was always practicing baseball.

He’d do his chores and he was gone.”

Hernandez attended San Diego High School, where he played for legendary

coach Dewey “Mike” Morrow and was All-Southern California with the

varsity team in 1937 and 1938. Hernandez also played with the

Hilltoppers in the Pomona

Tournament, an annual event that featured Southern California’s best

school teams, and attracted players such as Ted Williams, Jackie

Robinson and Bob Lemon. When Morrow's team clinched the Pomona

Tournament title for the third time in 1938, they gained permanent

possession of the $250 Stuart Carnation cup (previous wins were in 1934

and 1938). “Manuel Hernandez was an outstanding member of

the San Diego High School baseball team,” recalled Morrow. “He was a

fine boy to work with and very popular with all his teammates. He hit in

the ‘clean-up’ position for us, which indicates a heavy hitter, and was

directly responsible for many of our victories.”

Despite his athletic skills, Hernandez did not enjoy the academic side

of school, as Walter McCoy, who pitched for the Negro League Chicago

American Giants from 1945 through 1948, recalled. “One day he

[Hernandez] talked Freddy Martinez and me into playing hooky. We liked

school, but we really admired Nay because he was such a good ballplayer.

We were flattered he invited us to go with him. We walked to Fifth and

Laurel near Balboa Park. There were lots of big, beautiful homes. Nay

said he was taking us to one of them. That’s when we learned his older

sister was a maid for some rich people. She invited us in and fixed a

nice lunch. We never played hooky again, but I never forgot that lunch

in the rich people’s house.”

Outside of school, Hernandez played American Legion baseball with the

San Diego Post 6 team, and after graduation in 1938, he went on to play

with the Neighborhood House team - one of the top semi-pro teams in San

Diego. Meanwhile, his sister Valentina earned recognition as one of the

finest softball players in the county with the Coronado Lime Cola team.

Walter McCoy played against Hernandez on the sandlots. “Sandlot ball in

San Diego was top notch,” recalled McCoy. “I was with Cameron’s Café and

we met Neighborhood House for the city championship in ’40. We played at

University Heights, where Ted Williams played as a kid. The place was

packed because we were both good teams. Nay was a consistent hitter. He

always made contact and had pretty good power. You had to be careful

pitching to him. [He] was a very quiet guy, easy going, never gave any

trouble, but he was tough. Some people misread him and made the mistake

of pushing him too far. If you got in a fight with him, you were in

trouble. All the Hernandez boys were boxers and Nay never lost a fight.”

In 1940, Nay married Lucy Villa, and the couple had a son later that

year named Manuel (known as “Baby Nay”). “I remember the first game

after he got married,” recalled Jesus “Jesse” Ochoa, a Neighborhood

House teammate. “He swung and missed the first pitch. He swung so hard

at the second pitch that he fell down. We yelled at him: ‘That’s what

happens when you get married, Nay.’”

By 1944, Hernandez — who had not been drafted by the military due to a

heart murmur was playing ball with the Rohr Aircraft Corporation team in

the County League. The Pacific Coast League — just one level below the

majors — was one of only 12 minor leagues in operation due to the

manpower shortage and war restrictions, and San Diego Padres manager

George Detore was desperate for players. When he saw Hernandez play in a

Padres exhibition game against Rohr Aircraft, he offered the young

outfielder a contract. Detore paid Hernandez $250 a month and he joined

the Padres for spring training, showing his ability against powerhouse

military and defense plant teams and earning a spot on the roster for

the regular season.

On Opening Day, April 8, 1944, in front of 5,000 hometown fans at the

Padres’ Lane Field ballpark, Hernandez trotted out to left field for his

first taste of professional baseball. Batting sixth in the line-up

against the Oakland Oaks, he went 1 for 2, and scored a run in the

Padres 8–5 win. A week later, on April 15, again playing against

Oakland, Hernandez went 2 for 4 with a triple as San Diego won, 8–3. He

enjoyed his best game at the plate against Seattle on April 20, going 3

for 6 with a double in the Padres 3–2 win over the Rainiers.

Manuel, Jr., would watch his father play at Lane Field. “I remember my

Uncle Chapo would put me on his shoulders and jump over the seats to go

down to the field,” he recalled. “I was a little guy and it scared me,

but my dad would come to the fence. He’d hand me over the fence. My dad

would hug me and hand me back to my uncle.”

Defensively, Hernandez was sensational. “He could run like a deer,” said

Joe Valenzuela, also a rookie with the Padres in 1944.

Valentina Hernandez also recalls her brother’s defensive abilities. “I

remember him running for a long fly ball at Lane Field,” she said. “He

caught it leaping over the fence, but he hung on to it.”

Despite his defensive prowess, Hernandez struggled at the plate against

the Coast League pitchers and batted a lowly .207 in the 30 games he

played for the Padres.Hopes of a second season in professional baseball

were dashed when Hernandez received his draft call on August 8, 1944.

“The twist in the Nay Hernandez story is that he would not have gone

into the Army had he not played professional baseball,” said San Diego

baseball historian Bill Swank. “When he was able to play for the Padres

— who were desperate for warm bodies in 1944—the draft board decided

that he must be able to carry a rifle, too.”

“I saw Nay before he left,” recalled McCoy. “I was home on leave and he

was in his uniform saying good bye to his friends at the barber shop.”

When Hernandez left his young wife and son for basic training it was

early morning. “It was still dark outside,” recalled his son, “and my

dad was wearing his Army uniform. He had his duffle bag. I remember he

told me, ‘Now, you take good care of your mother, because I don’t think

I’m coming back.’ I was just a little kid and didn’t know what he

meant.”

Not long after Hernandez got into the service the Germans made their

last major offensive in the Ardennes in Europe, later known as the

Battle of the Bulge. America put all her available troops into the

European campaign and, just three months after joining the Army, Private

Hernandez was in Germany as a replacement with the 376th Infantry

Regiment, 94th Infantry Division. The division had been in the European

Theater since August 1944, and had originally been in Brittany, France,

where it was responsible for containing some 60,000 German troops

besieged in the Channel ports of Lorient and Saint-Nazaire. On New

Year’s Day 1945, the division headed northward to help hold the Third

Army front, where it found itself in the thick of the coldest winter in

Europe in years.

Occupying a sector between the Moselle and the Saar rivers—the sole spot

of German soil held by American troops at the time—conditions for a

young man from San Diego, California, were alien. With night

temperatures falling to around zero degrees Fahrenheit, his top

priorities were keeping his head down in foxholes, and finding ways to

stop his feet from freezing. The division had an epidemic of trench

foot.

On January 14, the 94th Infantry Division — known as “Patton’s Golden

Nugget” — went on the offensive and seized the German towns of Tettingen

and Butzdorf. The following day, Nennig was taken, but strong Nazi

counterattacks followed, and the towns changed hands several times

before being finally secured. Moving east, the division took Sinz in

early February, and launched an attack across the Saar River. By the

beginning of March, the division was 700 miles further south,

spearheading the Third and Seventh Armies’ drive to the Rhine. “We are

pretty dam [sic] busy,” Hernandez noted in a letter home, “and we are

moving so dam [sic] fast I haven’t much time to write. We’ve been taking

town after town.”

Around March 20, 1945, the 376th Infantry Regiment was called upon to

capture the industrial city of Ludwigshafen, one of Germany’s prize

chemical producing centers. The city had been a prime target for

strategic bombing by the Allied air forces because its factories

produced much of Germany’s ammonia, synthetic rubber, synthetic oil and

other vital chemicals. The city’s railroad yards were important targets

too, and hundreds of small factories produced war materials, such as

diesel engines for submarines. When the 376th Infantry Regiment entered

Ludwigshafen they were met with an artillery attack and by strong

resistance from fanatical German troops defending their homeland in the

rubble and ruins of the city streets.

Fighting against snipers, concealed anti-tank guns and cellar

strongholds, Private Hernandez was among many young Americans who were

killed before Ludwigshafen was taken on March 24, 1945. Unfortunately,

for Hernandez, a week after his death the 94th Infantry Division was

pulled out of action and sent to Willich, Germany, for Occupation duty.

On April 3, 1945, a Western Union telegram was delivered to Mrs.

Gregoria Hernandez in San Diego, advising “that your son Pvt Hernandez

Manual P was killed in action in Germany.”

“I remember my mother crying,” recalled Manuel, Jr. “I’d never heard her

crying like that before. She was wailing. I figured it out when she took

me to my grandparents’ home down by 27th and Newton. Everybody was

crying. That’s when I realized my dad was never coming home.”

Several days later, Gregoria received the last letter her son wrote. It

was dated March 5, 1945, and written from “Somewhere in Germany.” In the

letter, Hernandez asked his mother not to worry and said he was taking

good care of himself, but if anything should happen to him, “the

government will let you know about it as soon as possible.” He added,

“The Lord is watching over me because I had some close deals and I was

praying to God that the next one would land somewhere else.” In closing,

Hernandez asked for his love and kisses to be given to all his family.

His last sentence was, “So may God bless you all at home and be with you

at all times. Your son, Nay.”

“Manuel Hernandez will always be remembered as a fine example of young

manhood,” wrote Mike Morrow after hearing of Hernandez’s death. “[We]

will remember him for what he was, a fine clean boy, and a splendid

competitor. He gave his life, fighting, that other boys might take part

in athletics in years to come, in this great democratic country of

ours.”

Hernandez was buried at the United States Military Cemetery in

Luxembourg, with full military honors. Three years later — at the

request of the family — his body was returned to his hometown. On August

16, 1948, final rites for Private Hernandez were conducted at the First

Nazarene Church. His body now rests at Greenwood Memorial Park in San

Diego.

“I like to use my full name: Manuel P. Hernandez, Jr.,” his son

explained recently, “Because I am very proud to be named after my

father. I could never accomplish what he accomplished, but I’m also very

proud of my mother. She was Rosie the Riveter. She worked in an aircraft

factory during the war. Women who lost their husbands had to work and

raise their kids. They sacrificed and I don’t think they get enough

credit. If it wasn’t for my mother, I wouldn’t be who I am.”

There is a rather unusual but pleasant postscript to this story. In

February 1996, Tara McCauley, who was hoping to find her father,

contacted the San Diego Padres. All she knew was that her grandfather,

Manuel “Nay” Hernandez, had played for the Padres many years before.

Tara was the daughter of Hernandez’s son, and baseball historian Bill

Swank began the search for Manuel Jr. When he eventually tracked him

down, father and long-lost daughter were reunited. Tara’s grandmother

had taken Tara away from Manuel Jr., shortly after she was born, and he

had no contact with her again. “Because of baseball, my father found my

daughter for me!” said Manuel Jr.”

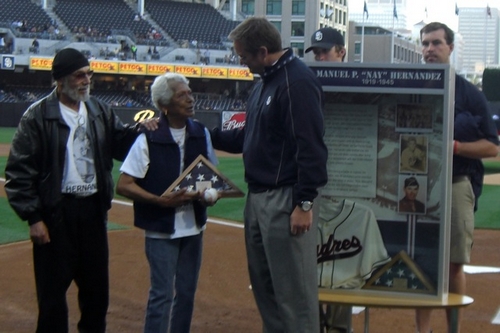

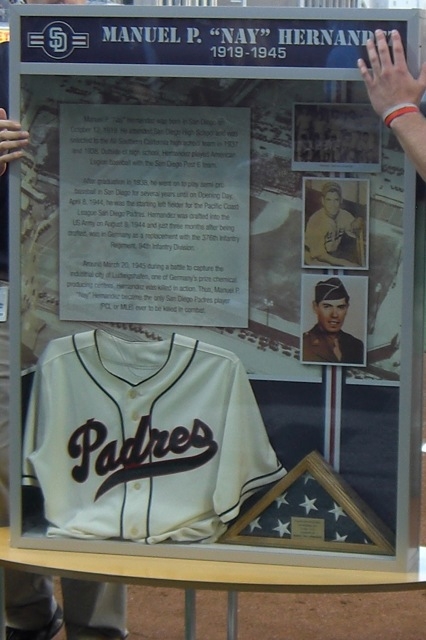

Sixty-five years after his death, on June 14, 2010, Hernandez was

honored by the San Diego Padres. The team placed a plaque in his memory

in the “military zone” beneath the right field stands at Petco Park. The

memorial was unveiled during pregame ceremonies.

|

Year |

Team |

League |

Class |

G |

AB |

R |

H |

2B |

3B |

HR |

RBI |

AVG |

| 1944 | San Diego | PCL | AA | 30 | 82 | 9 | 17 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 5 | .207 |

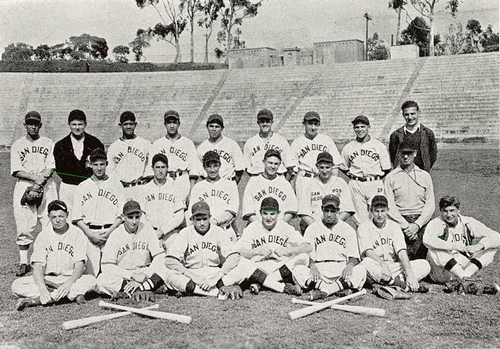

Nay Hernandez (front row, third from right) with the 1939 San Diego High School baseball team

Nay Hernandez with the Cramer's Bakery team (Hernandez id back row, second from right)

Nay's sister, Tina, and son, Nay, Jr., are presented with the American flag by Padres' president Tom Garfinkel on Memorial Day 2010 at Petco Park

The Nay Hernandez display featured in the Padres' Salute to the Military exhibition beneath the right field stands at Petco Park

Special thanks to Bill Swank for all his help with this biography and the photos. Thanks also to Astrid van Erp for help with photos for this biography.

Date Added January 31, 2012 Updated Updated August 2, 2017

Baseball's Greatest Sacrifice is associated with Baseball Almanac

Baseball's Greatest Sacrifice is proud to be sponsored by