Charlie Frye

| Date and Place of Birth: | July 17, 1913 Hickory, NC |

| Date and Place of Death: | May 25, 1945 Hickory, NC |

| Baseball Experience: | Major League |

| Position: | Pitcher |

| Rank: | Private |

| Military Unit: | Company D, 221st Battalion US Army |

| Area Served: | United States |

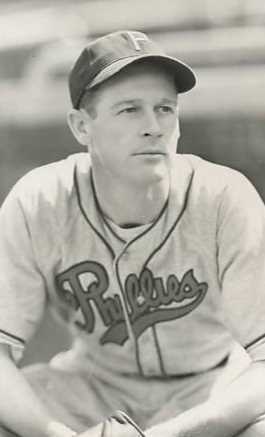

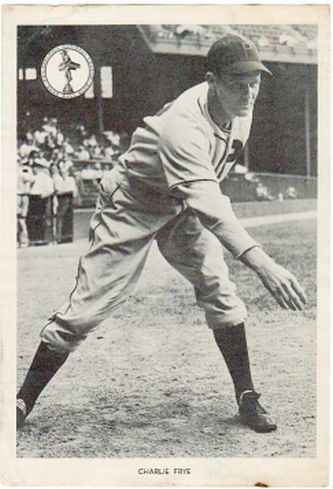

Charlie Frye was 27 years old when he made his big league debut with the Phillies in 1940. It proved to be his only season in the majors and within five years he would die from a ruptured ulcer. Between his days with the Phillies and his tragic death, Frye served a year in military service during World War II. Did this contribute to, or worsen, the medical condition that caused his demise? Quite possibly. Charlie Frye died just five months after being discharged from the army.

Charlie Andrew Frye was born in Hickory, North Carolina on July 17,

1913. He was the fourth child of 29-year-old James P. "Perry" and

28-year-old Etta E. (nee Price) Frye. His older siblings were twin

brothers Boyd and Floy, and sister Gladys. Elmer, Gaither, Arthur and

Millie would follow over the coming 12 years.

Located between Charlotte and Asheville in Catawba County at the foot of

the Blue Ridge Mountains in North Carolina’s Piedmont region, Hickory

was a growing town in the first half of the 20th century. When Charlie

was born the town’s population was around 4,000. By 1930, it had risen

to over 7,000 and by 1940 there were more than 13,000 inhabitants. This

was largely due to the furniture factories, hosiery mills and textile

mills in Hickory and the surrounding area that provided a steady source

of employment. Charlie’s father was employed as a wagon driver,

carpenter and machinist at different times to support his growing

family. By the age of 16, Charlie's school days had ended and he was

working as a laborer in a chair factory living with his family at 934 S.

Hill Street, in the Highland district of Hickory.

When young Charlie wasn't working at the chair factory, he was playing

baseball. In the Carolinas in the 1930s, like many parts of the United

States, baseball was one of the few forms of entertainment available

during the long summer evenings, and large crowds gathered to enjoy the

deep-rooted rivalry between neighboring town teams, and, of course, the

fiercely competitive mill teams.

The first record of Charlie playing competitive baseball was as a

20-year-old pitcher with the 1933 Hickory Rebels of the semi-pro Western

Carolina League. The Rebels were the creation of outfielder Norman

"Pinkie" James, who was attending Duke University on a football

scholarship but wanted to play baseball during the summer months. The

team, which consisted of other Duke players as well as players from

local Lenoir-Rhyne College and the sandlots of Hickory, quickly gained a

large fan base and even introduced night games to the area.

Pinkie James embarked on an eight-year minor league career in 1934 and

the Rebels were managed by Hack Culbreth, clinching the Western Carolina

League title and winning the third annual Carolinas semi-pro

championship. Frye was back with the Rebels in 1935, but spent the best

part of the season 30 miles east of Hickory with the league champion

Statesville Weavers of the Tri-County League. As was commonly the

practice, it’s most likely that Charlie was given employment at the

local mill purely to acquire his ballplaying skills, and he was back

with the Weavers in 1936 as a key part of their pitching staff. Writing

in the Statesville Record in February 1936, sportswriter Alwyn Morrison

described Frye as "one of the speediest right-handed twirlers in amateur

ball, and ... a good hitter."

The Weavers finished the 1936 season with a 25-16-1 record behind the

Statesville Chairs and Stimpson Hosiery, but good enough to earn a spot

in the four-team play-offs. The Weavers swept Stimpson Hosiery in two

games to advance to the finals with Frye hurling seven innings and

allowing just two hits in the 10-0 final game. Despite Frye allowing six

runs in the opening frame of the best-of-seven series against the

Statesville Chairs, the Weavers clinched the championship title in six

games.

Aged 23 and making headlines in local baseball, Frye made the jump to

the professional game and signed with the Mooresville Moors in March

1937. A new entry in the Class D North Carolina State League, the Moors

were managed by former Philadelphia Athletics first baseman Jim Poole.

Frye and Poole had probably crossed paths in local baseball competition

during previous seasons and Frye made 27 appearances for a 10-7 won-loss

record and 3.17 ERA. His rookie year performance with the league

champion Moors was good enough to be selected for the North Carolina

State League all-star team and his season highlight was a 5-0 no-hitter

against the Newton-Conover Twins on June 26, striking out five and

walking one.

At the end of the season, Mooresville sold Frye to the National League

Boston Bees and he spent the 1938 campaign with the Evansville Bees of

the Class B Three-I League. He was the workhorse of the pitching staff

but produced unspectacular numbers with an 8-7 won-loss record and 4.57

ERA in a team-leading 34 appearances. It was to be his only season in

the Boston farm system. As a side note, an Evansville teammate, Hugh

Bedient, entered military service with the Army Air Corps in June 1939.

Charlie Frye had been the relief pitcher that replaced Bedient in his

first professional start. Bedient was killed on June 17, 1940, as a crew

member of a twin-engined Douglas B-18 Bolo bomber that left Mitchel

Field, New York, on a routine training flight, collided with another

bomber and crashed in flames in Queens, New York.

In 1939, Frye began the season with the Martinsville Manufacturers, an

independent club in the Class D Bi-State League. Illness kept him out of

action for a while, and he was optioned to the Snow Hill Billies of the

Class D Coastal Plain League in May. After seven appearances for a 2-2

record and 5.18 ERA with Snow Hill, Frye was returned to Martinsville,

where - playing again for skipper Jim Poole - he finished the year with

an impressive 10-3 record (winning nine games in a row) and 3.10 ERA.

Frye also got married during the summer of 1939. His bride was Grace

Ellen Heath of Snow Hill, and they were married in Martinsville on July

12. Although the wedding certificate states that Grace was 21, she was

in fact just 18. It was a brief marriage and by the beginning of 1940,

the couple had separated and Charlie started a relationship with

20-year-old Mary Strait of Martinsville.

The 26-year-old began the 1940 season with Martinsville - now a

Philadelphia Phillies farm team - but on June 3, after seven

appearances, he was sold to the Portsmouth Cubs of the Class B Piedmont

League (also a Phillies farm club). Frye made 10 appearances with

Portsmouth for a 7-2 record before getting the call to the big leagues

from the struggling Phillies.

By July 27, the Phillies were in last place in the National League with

a 29-54 record. Second-year manager Doc Prothro was looking to avoid the

100-plus defeats the Phillies had suffered the previous season and boost

a pitching staff that included Hugh Mulcahy, Kirby Higbe and Ike

Pearson. On July 28, 1940 - 11 days after his 27th birthday - Charlie

Frye made his major league debut in the first game of a doubleheader

against the Cincinnati Reds at Philadelphia's Shibe Park. With the

Phillies trailing 6-1 after seven innings, the five-foot-11-and-a-half

inch, 170-pound right-hander took the mound before 10,160 fans. With

Bennie Warren behind the plate calling the pitches, Frye allowed four

hits over two innings to finish the game, allowing a run in the ninth.

The following day, July 29, with just 1,000 hometown fans in attendance,

Frye made his second relief appearance, hurling two scoreless innings to

close out a 7-3 loss to the Cubs. He allowed a hit and a walk while

striking out two. "He's got a lot to learn yet, especially about how to

field his position," said Prothro to the Associated Press. "But we feel

it is best to have him with us this year in order to acquire the

experience he needs to help us in 1941."

On July 30, Frye appeared on the sports pages of the Philadelphia

Inquirer as the paper introduced the "country boy" to baseball fans.

"Phils' Rookie Hurler Took $10 Taxi Ride - at Expense of Club,"

announced the headline alongside a photo of the hurler. "When I come in

town I didn't know anything where to go," Frye told the Inquirer. "So I

got in one of them cabs and said, 'Take me out to Doc Prothro's.' Down

in Hickory everybody knows where everybody else lives, so I thought that

driver would know where Doc lived. Well, we rode around to some big

hotel. I got out and told the cabbie to wait 'cause I didn't want to get

lost. Nobody seemed to know Doc Prothro there so I came out and told the

driver to try some place else. We rode around some more and I heard that

meter clicking so I says, 'How much do I owe you?' He says, '$3.65,' so

I says, 'Go ahead let's see the town. I may not be here long and this is

going to be on the Phillies.' I told the driver I had $10. So we rode

around. This is sure a big city. Finally, he stopped the cab and said,

'Your ten dollars is used up, the ballpark is a block away.'"

On August 4, 1940, Frye made his first start for the Phillies in a home

game against the Pirates. He shutout the Pirates for three innings

before giving up a run in the fourth and two more in the fifth. A

two-run homer by Pirate third baseman Debs Garms in the seventh inning

signalled the end of the game for Frye who had allowed nine hits and

four earned runs. The Pirates won the game, 6-4.

On August 7, Frye made his third relief appearance, allowing an earned

run in one-third of an inning in a 6-3 loss to the Bees. Two days later,

on August 9, Frye was chosen to start an exhibition game for the

Phillies against their farm club - the Allentown Fleetwings of the Class

B Interstate League. Going the distance in an 18-5 rout by the big

leaguers, Frye allowed six hits and walked four.

After five days rest, he took to the mound again with a one inning

shutout relief appearance against the Dodgers at Ebbets Field on August

14. Six days later, on August 20, he was pitching in relief against the

Cubs, allowing a walk and no runs in a 4-0 loss. The following day,

August 22, Doc Prothro made the surprise decision to send Frye up to bat

against the Cubs in the 10th inning of a 5-5 tied game. With one on and

one out, Frye hit Ken Raffensberger's offering over the ivy-covered

outfield fence to win the game for the Phillies.

Perhaps the home run antics of the night before earned favor with

Prothro because he started Frye against the Cardinals on August 22 at

Sportsman's Park. The rookie failed to get beyond the first inning,

allowing four runs on four hits and four walks before Lefty Smoll came

in to finish the inning and the game.

His next appearance was on August 25, against the Reds at Crosley Field,

before 23,544 Cincinnati fans. With the home team leading, 6-5, Frye

relieved Hugh Mulcahy in the bottom of the fifth and hurled a solid four

innings of shutout ball, allowing no hits and walking one. The following

day, August 26, he made another relief appearance against the Reds.

After pinch-hitting for shortstop Bobby Bragan in the top of the eighth,

he kept the Reds scoreless in the bottom of the inning. Three days

later, on August 29, Frye pitched two innings in relief of Ike Pearson

against the Pirates at Forbes Field, allowing no runs on three hits and

a walk. His next stint on the mound was a six-and-one-third inning

relief appearance against the Bees at Braves Field on August 31. With

Boom-Boom Beck being unable to get himself out of the first inning after

giving up four runs, Frye allowed six runs on eight hits and two walks.

The following day, September 1, he made his third pinch-hit appearance.

Going into the game with a .333 batting average, he failed to get a hit

for second baseman Ham Schulte in the ninth.

On September 4, Frye made his third start for the Phillies before a

little over 18,000 hometown fans against the Dodgers. It was a solid

complete-game performance - his best of the season - allowing three runs

on nine hits and two walks while striking out six. However, Brooklyn's

Luke Hamlin shutout the Phillie batters on seven hits and handed Frye

his fourth loss. The following day, September 5, he made another

pinch-hit appearance, grounding into a double play against the Dodgers.

On September 10, Frye started his fourth game. He lasted seven innings

against the Pirates at Shibe Park, allowing four runs (two of them

unearned) on eight hits and a walk in what ended as an 11-1 loss, giving

Frye his fifth loss against no wins. Six days later, on September 16, he

made his penultimate appearance of the season, pitching the first five

innings of a home game against the Cardinals. He allowed three runs (one

unearned) on four hits and five walks, picking up his sixth loss.

Frye's final appearance of the 1940 major league season was on September

22, against the Dodgers at Ebbets Field. Relieving Si Johnson, who got

into a jam in the first inning, Frye fared little better and allowed six

runs (two unearned) in two innings on seven hits and a walk. Two days

later, on September 24, Mary gave birth to their daughter, Yvonne, back

home in Hickory.

The Phillies finished the 1940 campaign with a 50-103 last-place record,

50 games behind the Cincinnati Reds. Hugh Mulcahy had lost 22 games,

while Kirby Higbe was not far behind with 19 defeats. Charlie Frye had a

0-6 record in 15 games. He threw 50-and-a-third innings with five starts

for a 4.65 ERA. In 19 at-bats he had five hits for a .263 average.

As a final side note on the 1940 season. Two of Frye's Martinsville

teammates lost their lives in military service. Warren "Buddy" Blewster,

a pitcher from Mechanicsville, Alabama, was killed in action with the

marines at Guadalcanal in the Pacific on October 22, 1942. Fred Swift, a

pitcher from Norristown, Pennsylvania, who was also a teammate of Frye's

at Allentown in 1941, was killed on a routine training flight with the

Army Air Force near Blanco, Texas, on April 23, 1944.

In 1941, Frye spent spring training with the Phillies, but was optioned

to the Allentown Fleetwings at the start of the season - the team he'd

pitched against for the Phillies in an exhibition game the previous

season. The Allentown Interstate League campaign began on April 30, with

Harmon Shufro, a right-hander who had missed the entire 1940 season with

a sore elbow, chosen for the opener. Shufro got into immediate trouble

and gave up five runs before recording an out. Charlie Frye came in and

shut down the Reading assault but proceeded to allow three runs in the

second inning before settling down for the rest of the game. Frye proved

he still had a potent bat in the game, hitting a towering solo home run

over the left field scoreboard in the third. In his first start for

Allentown on May 13, Frye beat Hagerstown, 3-1, scattering seven hits.

He threw a 1-0 three-hitter against Harrisburg on June 11, and a 3-0

three-hitter over Bridgeport on June 15, winning the game with a 2-run

single in the second. However, on June 28, he gave up 22 hits in an 18-0

loss to Hagerstown. On July 2, he retired the first 18 Harrisburg

batters he faced, winning the game, 6-4, and threw a 1-0 four-hitter

against league-leading Hagerstown on August 10. Frye finished the season

with a 10-14 won-loss record 115 strike outs and a 4.25 ERA. He set

career high marks in games pitched (35), complete games (19) and innings

pitched (218). Used as a pinch hitter and outfielder in 26 games, Frye

batted .220 with 4 doubles, a triple and 4 home runs.

On October 6, 1941, Charlie Frye, along with Allentown players Stan

Stuka and Jim Dillingham, were declared free agents by baseball

commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis. Frye had already made it clear

that he would not be returning to Allentown in 1942. Stuka explained the

situation to the Allentown Morning Call on October 7. "When we came to

Allentown we were the property of the National League Phillies," he

said. "When the Phillies did not recall us at the end of the season,

Judge Landis made inquiries as to whether the Allentown club had

invested any money for us, and learning that such was not the case gave

[us] the option of either signing new contracts with Allentown or

becoming free agents."

Out of contract, Frye returned home to Hickory to contemplate his

future. Two months later, on December 7, 1941, the Japanese attack on

Pearl Harbor catapulted the United States into World War II and changed

the world of professional sports for the duration.

Everyone wondered if baseball would survive the war and in response to a

direct plea from Commissioner Landis, President Franklin D. Roosevelt

sent his now famous January 15 "Green Light" letter. In his

correspondence, Roosevelt said, "I honestly feel that it would be best

for the country to keep baseball going," and added that he would like to

see more night games that hard-working people could attend. Roosevelt

also noted that baseball could provide entertainment for at least 20

million people, and added that although the quality of the teams might

be lowered by the greater use of older players replacing young men going

into military service, this would not dampen the popularity of the

sport.

Nevertheless, there were ten fewer minor leagues starting the 1942

campaign and another five did not complete the season. Free agents

Charlie Frye and Stan Stuka, signed in January 1942, with the Wilmington

Blue Rocks, the Philadelphia Athletics farm team in the Interstate

League. Stuka, four years younger than Frye, was called for military

service in February and did not return to the game after serving with

the Army Air Force until 1945. Frye made 20 appearances as a relief

pitcher before being sold to the Statesville Owls of the Class D North

Carolina State League in July, where he was reunited with manager Jim

Poole. Frye was used sparingly with Statesville and released in August.

There are no records to show where Frye played baseball during the

summer of 1943. Mary gave birth to their second child, Gerald, in

Newton, North Carolina, on April 8, 1943, and when Charlie entered

military service in the winter of that year, he listed his profession as

"athlete", which suggests he may have been pitching for a semi-pro club.

Frye was 30 years old when he was inducted on November 10, 1943, and

entered service with the army at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, on December

1. As a private, training to be an antitank gun crewman, he spent the

next 12 months with Company D, 221st Battalion at Camp Blanding,

Florida, an Infantry Replacement Training Center (IRTC) that trained men

for both the European and Pacific theaters. On October 2, 1944, Charlie

and Mary were married in Newton, North Carolina.

On December 22, 1944, Private Frye was honorably discharged from

military service. His Report of Separation shows that he had served one

year, one month and 13 days, and that his character had been

"Excellent". His civilian occupation was shown as "Baseball Player",

and, in addition to $200 mustering out pay, he received $11.35 travel

pay to get him home to North Carolina from Florida. What is most

interesting, however, is that his weight is shown as just 154 pounds.

Frye's playing weight was listed as between 170 and 175 pounds. With his

height listed as 5-foot-11-and-a-half inches this would seem extremely

underweight and possibly suggests illness.

Charlie returned to Hickory, but was admitted to Hickory Memorial

Hospital just a few months later, suffering with a ruptured gastric

ulcer. Aged 31, he died at 3:30am on May 25, 1945. Charlie Frye was

buried on May 27, 1945, at the Friendship Lutheran Church cemetery in

Taylorsville, North Carolina. He was survived by his wife, Mary, and

their children, Yvonne and Gerald, who were four and two at the time.

Mary lived to the age of 88, and passed away at Memorial Hospital in

Martinsville in November 2007.

|

Year |

Team |

League |

Class |

G |

IP |

ER |

|

SO |

|

|

|

| 1933 | Hickory | Western Carolina | Semi-pro | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 1934 | Hickory | Western Carolina | Semi-pro | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 1935 | Hickory | Western Carolina | Semi-pro | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 1935 | Statesville | Tri-County | Amateur | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 1936 | Statesville | Tri-County | Amateur | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 1937 | Mooresville | North Carolina State | D | 27 | 161 | 57 | 73 | - | 10 | 7 | 3.19 |

| 1938 | Evansville | Three-I | B | 34 | 138 | 70 | 66 | - | 8 | 7 | 4.57 |

| 1939 | Martinsville | Bi-State | D | 20 | 116 | 40 | 56 | - | 10 | 3 | 4.34 |

| 1939 | Snow Hill | Coastal Plain | D | 7 | 40 | 23 | - | - | 2 | 2 | 5.18 |

| 1940 | Martinsville | Bi-State | D | 7 | 48 | 25 | 25 | - | 2 | 1 | 4.69 |

| 1940 | Portsmouth | Piedmont | B | 10 | - | - | - | - | 7 | 2 | - |

| 1940 | Philadelphia | National League | MLB | 15 | 50.1 | 26 | 26 | 18 | 0 | 6 | 4.65 |

| 1941 | Allentown | Interstate | B | 35 | 218 | 103 | 98 | 115 | 10 | 14 | 4.25 |

| 1942 | Wilmington | Interstate | B | 20 | 20 | 10 | - | 0 | 2 | - | |

| 1942 | Statesville | North Carolina State | D | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

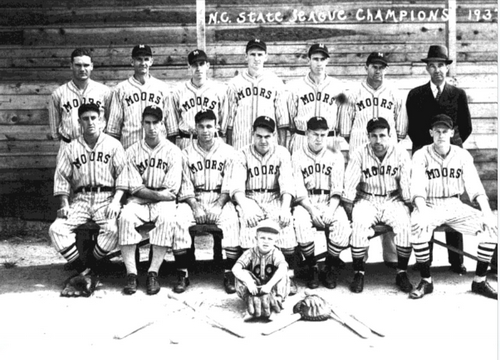

Charlie Frye with the Mooresville Moors in 1937. Frye is front row, far

right.

Date Added February 15, 2020

Baseball's Greatest Sacrifice is associated with Baseball Almanac

Baseball's Greatest Sacrifice is proud to be sponsored by