Sam Freeny

| Date and Place of Birth: | August 26, 1896 Salisbury, MD |

| Date and Place of Death: | December 23, 1944 San Fernando, Pampanga, Philippines |

| Baseball Experience: | Minor League |

| Position: | First Base |

| Rank: | Lieutenant-Colonel |

| Military Unit: | 7th Marine Regment and Headquarters Company, 1st Battalion, 4th Marine Regiment, US Marine Corps |

| Area Served: | Pacific Theater of Operations |

Samuel W. Freeny, the son of Samuel and Martha

Freeny (sometimes written Freeney), was born on August 26, 1896 in

Salisbury, Maryland. His parents, originally from Delaware, operated a

farm in Delmar, Maryland, situated in Wicomico County in the

southeastern part of the state. He had two older brothers – Barton and

Benjamin – and a sister – Bessie. Samuel was just three years old when

his father passed away in 1899, aged 38, and was nine when his eldest

brother, Barton, died aged 21.

A naturally gifted athlete,

Freeny played baseball at St. John’s College, situated at Annapolis, on

the

banks of the Severn river, a few

miles from the Chesapeake Bay. A left-hander, Freeny played first base

for St. John’s from 1914 to 1917, and was captain of the team his senior

year.

St. John’s had its own military

department and all students, except those physically disqualified, were

required to take part. “The

Military exercises … [give] to the students an erect and soldierly

bearing, of teaching them habits of neatness, order and discipline,

prompt and ready obedience, and

Off campus, Freeny pursued a

career in baseball and played in the minors during the summers of 1915

and 1916. In 1915, he was signed by the Hagerstown Blues of the Class D

Blue Ridge League, appearing in 56 games and batting an unmemorable

.168. In 1916, he joined the Hanover Raiders of the same league, but the

Raiders had 31-year-old Frank Rooney holding down first base. Rooney

played major league baseball with the Federal League’s Indianapolis

Hoosiers in 1914, and Freeny was released in June, joining the Frostburg

Demons of Class D Potomac League, where, in 40 games he batted .333.

When the Demons disbanded in August, Freeny returned to Hagerstown,

playing 18 games and batting .220.

Upon graduation from St. John’s

in April 1917, Freeny was admitted to the Marine Corps as a second

lieutenant. He attended Marine Officers’ Training School at Quantico,

Virginia, for three months, then trained at Parris Island, South

Carolina, before joining the 7th Marine Regiment at

Guantanamo Naval Base in Cuba. By 1919, he had attained the rank of

captain and was stationed at the Marine Barracks at the U. S. Naval

Academy in Annapolis. Freeny remained for three years and played

baseball throughout state for the Marine Corps. Before returning to

Guantanamo Bay in 1923, he had got married, had a son – Samuel, Jr., -

and coached the St. John’s College baseball team. He went from Cuba to

Haiti in 1924, and assumed command of the Marine Recruiting Station in

Baltimore in August 1925.

His baseball skills were in

demand in 1926, and Freeny made a return to the minors that year,

despite being 29 years old. Back in Maryland on furlough, Freeny was

persuaded to play for the Salisbury Indians of the Class D Eastern Shore

League. To do this and avoid complications with the Marine Corps, he

played under the name of Samuel Wilson, although all the Indians’ fans

new he was Sam Freeny. In 35 games he led the league with a .390 batting

average and clubbed six home runs before being recalled to military

duty. So popular, was Freeny that the day before he left, July 14, was

“Sam Freeny Day” at the Indians’ Gordy Park, when he was presented with

a gold wristwatch.

“I always liked Sam Freeny,”

recalled longtime Maryland-area baseball coach Gerald Wilson, “He had

all the tools – hit, run, throw – and could play anywhere. That boy

hustled his heart out all the time.”

From 1925 to 1931, Freeny played

first base, assisted in coaching and captained the Marine Corps baseball

team at Quantico. The team assembled the best players in the Marine

Corps and played an all-college schedule of games as well as

inter-service tournaments. In 1926, he helped the Marine Corps win the

service world series in Philadelphia, beating the Navy two out of three

games, and batting .341 on the year. In 1927, he batted .506 with five

home runs in a 22-game schedule that included games against Vermont,

Temple and Gettysburg College. In 1928, 31-year-old Freeny helped the

Marine Corps win all its scheduled 17 games.

Freeny was also busy on the

semi-pro circuit during the summer months. In 1928, he was playing for

the semi-pro Hampden Club managed by former major league outfielder

George Maisel, as well as starring with the Fairfield Farm-Western

Maryland Dairy Club in the Interclub League, and still found time to

help the Eastport team to the Anne Arundel county baseball championships

in September.

In October 1928, he sailed to

Haiti with the Marines, where he served as a member of the Garde

d’Haiti, the local military force on the island, and returned to the

United States in February 1931, in time to captain the Marine Corps

baseball team at Quantico for the final time. At the conclusion of the

season he was sent to the Marine Corps Barracks in Philadelphia, and

remained there until 1935, including a short period of time attached to

the Civilian Conservation Corps.

In 1941, Freeny was promoted to

major in 1936, and was stationed at Quantico until 1940, when he saw

action in Haiti, when the Marines were called to quell revolutionary

disturbances. On July 20, 1940, Freeny left for Shanghai, China and was

made athletic director of the Shanghai garrison. Going back to his

baseball roots, he managed a Marine Corps team that defeated a team of

Shanghai athletes.

Freeny was promoted to

lieutenant-colonel and was assigned to the Marine Barracks, Olongapo

Navy Yard, Philippines in November 1941, as executive officer of

Headquarters Company, 1st Battalion, 4th Marine

Regiment. At approximately 0300 hours on the morning of December 8,

1941, word was received of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Reveille

was sounded and Freeny addressed the men of his unit while still in his

nightshirt.

On December 14, Japanese bombers

attacked the Olongapo Navy Yard and Subic Bay Navy Base. Ten days later,

the order was given to withdraw. Against invading Japanese troops the

11,000 defenders fought bravely for six months with their final battle

being conducted at Corregidor. During the battle, Freeny organized a

platoon of men he gathered from the Malinta Tunnel (a tunnel complex

used as a bomb-proof storage area and personnel bunker) to reinforce the

beleaguered 1st Battalion. One of the U.S. Army enlisted men he acquired

complained, "I've never fired a rifle before. I'm in the finance

department!" Freeny replied, "You just go out and draw their fire and

the Marines will pick them off."

Freeny was wounded on April 29,

and eventually captured by the Japanese after the fall of Corregidor on

May 6, 1942.

“I am sure that when he was

captured, there was one thing the Japs had trouble in taking from him –

something that my brother prized highly,” recounted his brother,

Benjamin, years later referring to the gold wristwatch he had been given

by the Salisbury Indians back in 1926. “I know that he would have fought

to keep the Japs from taking that watch from him.”

Held in inhumane conditions at

Bilibid prison in Manila for the next two years, 1,620 prisoners of war

(including 1,556 Americans) were then loaded onto the Oryoku Maru – a

Japanese passenger cargo ship that became renowned as one the “Hell

Ships” due to their horrendous living conditions and the many deaths

that occurred on board - on December 13, 1944, bound for Japan. As the

ship neared the naval base at Olongapo in Subic Bay, U. S. Navy planes

from the USS Hornet attacked the unmarked ship, causing it to sink on

December 15. As the prisoners tried to save themselves they were

machine-gunned from the deck by Japanese guards. Those that survived and

made it to shore were held for several days in an open tennis court at

Olongapo Naval Base, before being moved to San Fernando, Pampanga.

While at San Fernando, American

doctors pleaded with the Japanese to send the worst cases to a hospital

in Manila for urgent treatment. “We felt that they would be much better

off getting to a hospital,” recalled Colonel Curtis T. Beecher. “As we

loaded the patients into the truck, I remember standing there in the

darkness, thinking to myself, ‘Well, there are at least 15 prisoners who

in spite of their wounds are pretty lucky.’”

Among the 15, and the only one

who was a Marine, was a very frail Lieutenant-Colonel Freeny.

However, the men were not taken

to hospital in Manila. Instead, they were driven to a cemetery where

they were bayonetted, beheaded, and dumped into a mass grave.

News of Freeny’s death reached

his family in June 1945, but they were informed he had been killed

during the sinking of the Oryoku Maru. It was not until 1947, that the

truth was learned during war trials held in Yokohama, Japan. For his

part in the atrocity, Lieutenant Junsaburo Toshino – commander of the

prisoner of war escort guard, was found guilty of murdering and

supervising the murder of at least 16 men, and sentenced to death.

Shunosuke Wada – the official interpreter for the guard group whose

charges paralleled those of Toshino, was found guilty of causing the

deaths of numerous American and Allied prisoners of war by neglecting to

transmit to his superiors requests for adequate quarters, food, drinking

water, and medical attention. Wada was sentenced to life imprisonment.

Following the discovery of Sam

Freeny’s remains, his widow, Bertha, requested he be returned to the

United States. Sam Freeny is buried at the United States Naval Academy

Cemetery in Annapolis, Maryland. A marble cross in memory of Freeny also

stands at St. Marks Episcopal Church Cemetery in Laurel, Delaware, and

was dedicated in April 1948. He attended the church as a child and his

parents are buried there.

His widow passed away in 1980,

aged 87, and is buried with Sam. Tragically, there only child, Sam, Jr.,

was killed in a car crash in September 1956, aged 34.

Dedicated in 1998, the World War

II Memorial at Annapolis honors Maryland citizens who gave their lives

in the conflict. Black stone panels display the engraved names of 6,454

Maryland military men and women, including Lieutenant-Colonel Samuel

Freeny.

|

Year |

Team |

League |

Class |

G |

AB |

R |

H |

2B |

3B |

HR |

RBI |

AVG |

| 1915 | Hagerstown | Blue Ridge | D | 56 | 179 | 19 | 30 | 6 | 0 | 1 | - | .168 |

| 1916 | Hanover | Blue Ridge | D | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 1916 | Frostburg | Potomac | D | 40 | 159 | 24 | 53 | - | - | - | - | .333 |

| 1916 | Hagerstown | Blue Ridge | D | 18 | 59 | - | 13 | - | - | - | - | .220 |

| 1926 | Salisbury | Eastern Shore | D | 35 | 141 | - | 55 | 6 | 1 | 6 | - | .390 |

Freeny’s 1926 season is often accidently credited to Samuel “Mike” Wilson, who played for Saliisbury in 1927 but not 1926. The confusion lies in Freeny playing under the name of Sam Wilson.

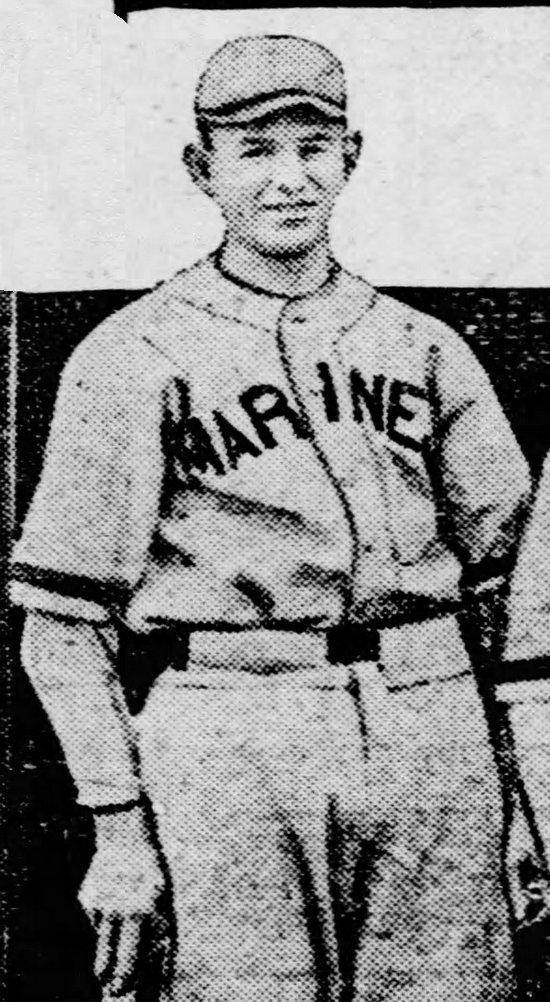

Sam Freeny with the Marine Corps baseball team mascot, a bulldog named Private Pagett

Thanks to Jack Morris for bringing Sam Freeny to my attention.

Date Added: September 16, 2020

Baseball's Greatest Sacrifice is associated with Baseball Almanac

Baseball's Greatest Sacrifice is proud to be sponsored by