George Bogovich

| Date and Place of Birth: | September 15, 1914 Masontown, PA |

| Date and Place of Death: | April 26, 1945 Okinawa |

| Baseball Experience: | Minor League |

| Position: | Pitcher |

| Rank: | Private First-Class |

| Military Unit: | 106th Infantry Regiment, 27th Infantry Division US Army |

| Area Served: | Pacific Theater of Operations |

Bogovich was one of many eccentric ball players that showed brief glimpses of brilliance in Organized baseball during the 1930s. A hard-throwing left-hander with a shaggy mop of black hair, an unbuttoned jersey and suffering recurring bouts of homesickness, he always had a word or two for the local reporters. By 1945, his brief career in baseball was a distant memory, the world was at war and Bogovich was on his way to the Pacific as a private first-class in the United States Army.

George E.

“Bogey” Bogovich was born on September 15, 1914 in Masontown,

Pennsylvania. His parents, Mike and Mary, were immigrants from central

Europe, arriving in the United States at the turn of the 20th

century. Mike worked in the coalmines of western Pennsylvania,

supporting a family of five daughters and two sons. The two boys George

and Eli - were the last-born children. George followed his father into

the coalmines, but baseball was his true love and something for which he

possessed a great talent. Having pitched for the local American Legion

junior team in the late 1920s, he hurled for sandlot teams, including

Edenborn in the Dice-Spalding League in 1932, Miraclean of the same

league in 1933, and Republic of the Industrial League in 1934. By 1935,

he was pitching for Filbert of the Western Pennsylvania League and Royal

of the Tri-County League, attracting a great deal of attention from

local scouts who were keen to sign the hard-throwing lefty.

Bogey signed

with the Charleroi Tigers of the Class D Penn State Association in

August 1935, as they tried in vain to secure a place in the play-offs.

The 20-year-old showed promise as his raw talent produced a 6-0

three-hitter over the Washington Generals on September 1, securing a

contract for the following year. In 31 appearances for the Tigers in

1936, Bogey had 8 wins against 13 losses with a 5.23 ERA. His season

highlight was a 5-0 six-inning no-hitter against the McKeesport Tubers

on August 26.

Bogey was

invited to spring training with the Fort Worth Cats of the Class A1

Texas League for 1937, a huge jump from Class D ball of the year before.

Despite showing promise his spring performance was hampered by concern

over the critical illness of his father, which led to him leaving the

club and returning to Pennsylvania. Although he was still the property

of the Fort Worth ball club, Bogey began working in the coalmines. “I

get down in the mine,” he later recalled, “but I don’t dig no coal. I

long to pitch some more. So I hit the road again.”

But Bogey

didn’t hit the road as far as Fort Worth, Texas. In fact, he didn’t hit

the road particularly far at all. He chose instead to remain in the

local area and play for semi-pro teams around Pennsylvania and West

Virginia, often using a false name to hide his connection with the Fort

Worth club. “Just when I would get settled with some semi-pro outfit,”

he explained, “a major league scout would come nosing around, and I

would have to leave in the night. And I would get in a new town and look

in the box scores in a paper and select me another name and then report

to a local semi-pro manager.”

By the late

summer of 1937, Bogey was pitching for Edenborn, the Fayette

(Pennsylvania) County champions. Using the alias, George “Judy” Steiner,

Bogey threw a no-hitter and struck out 18 for Edenborn in his first

appearance in the NABF (National Amateur Baseball Federation) tournament

at Dayton, Ohio, and was mobbed by scouts. The Dayton Herald of

September 13 featured an impressive article about “Steiner” that

included three photographs of the youngster. But Billy Doyle, the

Detroit scout, knew exactly who “George Steiner” was. “There’s no use

fooling with that kid,” Doyle told the other scouts. “His name’s

Bogovich, and he belongs to Fort Worth.” Bogey and the Edenborn team

were subsequently thrown out of the tournament for using an illegible

player.

After

working the coalmines during the off-season, Bogey was back at the Fort

Worth Cats’ spring training camp in 1938. “Bogovich…is reported just

about as fast as they come,” declared the Fort Worth Star-Telegram in

March, and the 23-year-old made the team’s roster for the start of the

regular season, leading to a host of crazy antics for sports writers to

devour. In one game, he threw the ball clear over catcher Vern Mackie’s

head and into the grandstand. Mackie rushed out to the mound to find out

what the trouble was. “Nothing,” Bogey calmly replied. “I was all right,

just taking my time getting a good windup. When I looked down at the

plate, that big batter had a mean look in his eye and was drawing that

bat back. I knew he’d hit one over the fence for sure. So, I just put

the ball where he couldn’t reach it. I fooled him, didn’t I?”

Another

time, Bogey stated that he thought that pitchers’ arm troubles were

mostly mental. “Me, I never think of my arm,” said Bogey, “so it never

bothers me...I never wear no jacket between innings or rub my arm or

nothing. In fact, I don’t know I got an arm until I get out there and

start chucking.”

On the Cats’

first road trip, Bogey’s restaurant bill included cigarettes, cigars,

chewing tobacco and magazines. When the team’s business manager

explained that the club was not responsible for such items, Bogey

replied: “Okay, but you hadn’t ought to talk like that to a poor,

overworked, hard-up rookie.”

After once

telling Vern Mackie, who, at the time, was probably the best catcher in

the Texas League, that he

was doing something wrong behind the plate, Mackie told Bogey, “Listen

punk, all you have to do is try to get that ball over the plate, some

way or another. I’ll catch ‘em. Anyway, I play ball in leagues where

they wouldn’t even sell you a ticket to get in the park.”

Bogey

struggled to get the ball over the plate and made six appearances during

the early part of the year for an ERA of 15.43. He then went AWOL again

on June 3. Bogey returned five days later and told the Cats’ business

manager Cecil Coombs that he’d like to play for Lake Charles (the Cats’

Class D affiliate in the Evangeline League) if the pay there was the

same as at Fort Worth. Bogey was promptly suspended.

It was the

end of Bogey’s minor league career, but his baseball-playing days were

far from over. Working in the coal mines during the off-season, Bogey

made a name for himself as the best pitcher in western Pennsylvania,

pitching for Edenborn, Isabella and Buffington in Fayette County’s

semi-pro Big Ten League until being inducted in the army in November

1943. The following February, with overseas service looming, Bogey

married 24-year-old Emaline Ciaramella. They made their home, albeit

briefly in Edenborn, Pennsylvania.

His younger

brother, Eli, had entered military service with the army the year

before. Despite serving with different divisions, their lives were on

course for a series of tragic similarities.

Private

First-Class George Bogovich was with the 106th Infantry

Regiment of the 27th Infantry Division, when he arrived at

Okinawa on April 9, 1945. Only 340 miles from mainland Japan, Okinawa

was the final Allied amphibious landing of the war. It was also the

largest in the Pacific campaign and proved to be the bloodiest. Just

over two weeks later, on April 26, during the battle to secure Machinato

Airfield from the Japanese, Bogovich was killed in action. He was 30

years old and was awarded the Bronze Star and Purple Heart.

The day

after Bogey’s death, his 26-year-old brother, Eli, arrived at Okinawa

with the 306th Infantry Regiment of the 77th

Infantry Division. Also, a private first-class, Eli was awarded the

Bronze Star twice before being killed in action on May 19. In the space

of three weeks, Mike and Mary Bogovich had lost both their sons on a

remote island in the Pacific, 7,500 miles from Pennsylvania. Emaline had

lost her husband of just 14 months*.

Both George

and Eli remain on an island in the Pacific. They are buried at the

National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, better known as the

Punchbowl, in Honolulu, Hawaii. George was laid to rest at Plot D16 on

March 24, 1949. Eli was laid to rest at plot D38 a day later.

In July

1945, ceremonies were held for Bogey before the Dice-Spalding League

game between the Edenborn and Johnny’s Inn teams. A further ceremony was

held in 1946, before a Big Ten League game and Joe Petko, league

president, called it “the most impressive ceremony I have ever seen,

befitting every district ball player giving his life during World War

II.” In 1954, Bogey was among the first inductees in the Big Ten Fayette

County Baseball Hall of Fame.

The closing

of western Pennsylvania coal mines starting in the 1950s, saw the demise

of semi-pro baseball and with it went the memories of players like

George “Bogey” Bogovich. Seventy-seven years after his death, Bogey is

all but forgotten. He hasn’t been inducted in the Fayette County Sports

Hall of Fame, which was founded in 2008, and it was by chance that my

friend, Jack Morris, stumbled across Bogey’s name. He has been added to

the Baseball’s Greatest Sacrifice website where his exploits on the ball

field and ultimate sacrifice on the battlefield will be preserved for

all future generations.

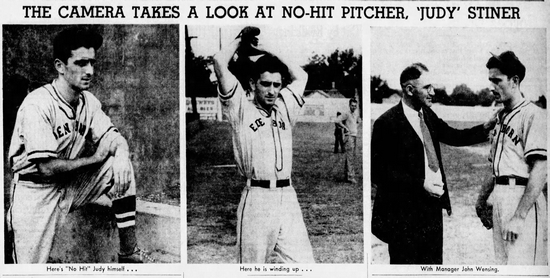

Bogovich following his no-hitter at NABF tournament when he played as

George "Judy" Steiner

Bogovich is front row, far right, in this photo of the 1942 Buffington

Big Ten team

Date Added April 6, 2022

Thanks to Jack Morris for "discovering" George Bogovich.

Baseball's Greatest Sacrifice is associated with Baseball Almanac

Baseball's Greatest Sacrifice is proud to be sponsored by