Dick Aldworth

| Date and Place of Birth: | October 1, 1897 Augusta, GA |

| Date and Place of Death: | September 18, 1943 Kelly Field, San Antonio, TX |

| Baseball Experience: | Minor League |

| Position: | Pitcher |

| Rank: | Colonel |

| Military Unit: | USAAF |

| Area Served: | Europe and United States |

Dick Aldworth was a semi-pro star in San Antonio before going to spring training with the Philadelphia Athletics. His minor league career was interrupted by World War II and he served as a fighter pilot on the Western Front. Aldworth remained in military service for 22 years and returned in 1941, to help his friend, Claire Chennault form the Flying Tigers.

Richard T. “Dick” Aldworth, the son of Thomas and Agness Aldworth, was

born on October 1, 1897, in Augusta, Georgia. His father died on April

25, 1906,

and Richard and his mother moved to San Antonio, Texas, to live with her

parents, James and Katherine Quinn.

Aldworth attended St. Anthony's Apostolic School (commonly known as St.

Anthony's College) - where he was an outstanding pitcher - and

attended St. Mary's University in San Antonio in 1914.

By the time of his graduation, Aldworth was a well-known figure within

the San Antonio baseball community. The tall, redhead, who played

baseball for the Knights of Columbus and hurled a two-hitter against the

Signal Corps team at nearby Fort Sam Houston in April of that year, was

signed by Connie Mack’s Philadelphia Athletics in October 1915. To

celebrate, he hurled a 5-0 no-hitter against the Harlandales, for the

Ahrens & Ott semi-pro team on Oct 31, and spent the winter months

captaining the Knights of Columbus basketball team before reporting to

the Athletics’ spring training camp at Jacksonville, Florida, in March

1916.

Aldworth was used sparingly during spring training, but turned in a

solid performance in April against the University of Tennessee. Hurling

eight innings before the game was halted due to rain, Aldworth beat the

Volunteers, 6-0, allowing just one hit and fanning 13.

When the regular season opened, Aldworth was assigned to the New Haven

Murlins of the Class B Eastern League. Managed by former Athletics

second baseman, Danny Murphy, and playing alongside big leaguers Rube

Bressler, Frank Woodward, Dizzy Nutter, Red Shannon and Mickey Devine,

Aldworth made nine appearances for a 4-4 won-loss record with 64 innings

pitched. By July, however, at a time when the Athletics could have used

a decent pitcher (they were 19 and 71 by the end of July and finished

the season with an abysmal 36-117 record), Aldworth was back home in San

Antonio, nursing a sore arm.

By the time the 1917 baseball came around, America had entered the First

World War, and Aldworth had enlisted at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio,

Texas. His professional baseball days were behind him but he was still

playing, albeit with the Army’s headquarters team at Fort Sam

Houston, causing as much damage with his bat as with his pitching. On

April 29, Aldworth had a home run, two triples and two singles in a 21-3

thrashing of the Aeros at Fort Sam Houston. In May 1917, he attended the School of Military Aeronautics at

the University of Texas, Austin, for ground flight instruction with a

view to becoming a pilot. He went on to train with the Aviation Section

of the Signal Corps at Fort Wood, New York, until October 1917, then

left the United States for France, and learned to fly with the

Headquarters Detachment, 3rd Aviation Instruction Center at Issoudun

Aerodrome. Aldworth soloed in two hours and 35 minutes in December 1917.

From France, he went to Italy and continued to train at the 8th Aviation

Instruction Center in Foggia, also teaching Italian pilots to fly (Italy

was an ally during the First World War).

In July 1918, Lieutenant Aldworth joined the 213th Aero Squadron, 3rd

Pursuit Group, in France, and took part in the St. Miehel, Meuse and

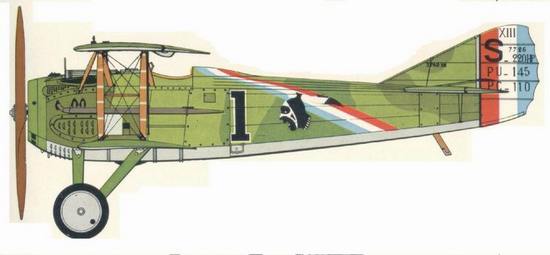

Argonne campaigns. Aldworth flew the French-designed Spad S.VII and Spad

S.XIII biplanes, engaging and clearing German aircraft from the skies

and providing escort to reconnaissance and bombardment squadrons over

enemy territory. He also attacked enemy observation balloons, and

performed close air support and tactical bombing attacks of enemy forces

along the front lines. On November 4, 1918, Lt. Aldworth shot down a

German plane northwest of Verdun, but a few days later he himself was

brought down over German territory and taken prisoner. He managed to

escape from the prisoner-of-war camp in Karlsruhe, Germany, and returned

to allied lines, although news of his safe return did not reach

concerned friends and family in San Antonio until mid-December, up to

which point he had been reported missing in action.

The type of plane Lt. Aldworth flew with the 213th Aero Squadron

With the war over, Aldworth served with the Army of Occupation in

Germany with 138th Aero Squadron. In Coblenz, in July 1919, he was

piloting a Spad biplane for the Polish government who were contemplating

purchasing the plane. Whilst putting the plane through various

maneuvers, the engine failed. Aldworth attempted a landing, but when he

realized he would not be able to clear some fast-approaching trees – and

just a few feet above the ground - he jumped for his life. As the

biplane crashed into the trees and was destroyed, Aldworth landed with a

thud and was lucky to escape with little more than a broken ankle.

Aldworth returned to the United States in September 1919, and remained

in the Air Service. He was stationed at Fort Sam Houston until December,

then moved to Kelly Field - at that time the center for advanced

training, where Claire Chennault of “Flying Tigers” fame, was also an

instructor. During the 1920s, while in service, Aldworth continued to

play baseball in the San Antonio area with the San Antonio Independents

and the Alamo-Peck Indians.

On July 11, 1922, Aldworth suffered further injuries as a result of a

flying accident. He was piloting a two-seater plane at Camp Hancock,

near Augusta, Georgia, that crash-landed due to engine failure. Aldworth

suffered a fractured skull and lacerations to his body, while his

passenger, Major P. E. H. Brainard, received a fractured arm and cuts to

his face.

Yet another accident occurred on December 12, 1926, and on this

occasion, Aldworth’s disregard for his own safety spared the lives of

many others. Taking off from Mitchel Field, Long Island, 1st Lieutenant

Aldworth’s pursuit plane stalled as it was flying towards Rockaway

Beach, Queens. Rather than land on the beach and risk killing civilians,

he ditched the plane in the sea. Despite the plane somersaulting when it

hit the water, Aldworth was able to walk away from the accident with

little more than a scratch on his head.

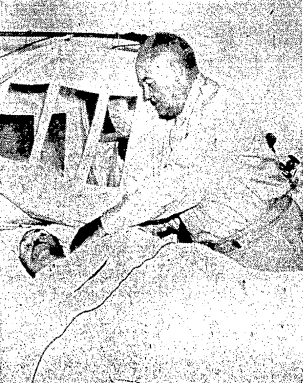

Lt. Aldworth's plane in the water after crashing near

Rockaway Beach, New York, on December 12, 1926.

In January 1929, Aldworth was granted a leave of absence from

military service to act as temporary superintendent at Newark

Metropolitan Airport, having complete authority of all planes flying

from that airfield. His leave expired in July 1929, and he returned to

the air corps, stationed at Langley Field, Virginia. In August 1929,

Aldworth landed at Amboy Airport, near Syracuse, New York, in a Curtiss

P-6 Hawk, to be greeted by H. O. "Bull" Nevin. The two had served

together in France and not seen each other since Aldworth was shot down

behind enemy lines in November 1918. Until then, Nevin believed Aldworth

to be dead.

In January 1930, after 22 years of service, Aldworth retired from active

duty and returned to Newark Metropolitan Airport as supervisor. Not

counting his time in France, Aldworth had had more than 2,800 hours in

the air.

For the next ten years, Aldworth served as supervisor at Newark. On

August 25, 1932, he was on hand at Newark as Amelia Earhart became the

first woman to complete a non-stop transcontinental flight, taking off

from Los Angeles the day before. On November 8, 1934, as official timer

for the National Aeronautical Association, he witnessed Eddie

Rickenbacker break the transcontinental record for transport planes in a

12-hour flight from Burbank, California. On May 9, 1935, he was on hand

to record the official time of Amelia Earhart's non-stop flight from

Mexico City. The 2,100-mile journey took 14 hours, 28 minutes and 50

seconds, covering the perils of the Mexican mountains, the long stretch

of the Gulf of Mexico and up the Atlantic Seaboard. For six years he was

chairman of the New Jersey State Aviation Commission and consultant for

the Bureau of Air Commerce, considered the leading expert on air traffic

control.

On June 5, 1937, in recognition of his act of bravery 11 years earlier

at Rockaway Beach, Aldworth was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross

in a ceremony at Mitchel Field by Major General Frank R. McCoy,

commanding general of the second corps area.

By 1940, Aldworth was 42 years old, and his health was failing. In 1941,

he was admitted to Walter Reed General Hospital, suffering from

non-Hodgkin lymphoma (cancer of the lymph glands). Despite this, in

April of that year he was called upon to serve his country again. Claire

Chennault was putting together the American Volunteer Force, or “Flying

Tigers”, to help the Chinese fight the Japanese in the air. He

desperately needed to recruit pilots and mechanics. Aldworth was seen as

the perfect person for the job and Chennault telephoned him at Walter

Reed Hospital, explaining the problem and why the group was being

organized. Although gravely ill, Aldworth agreed to help Chennault and

his team.

Between April and December 1941, under the umbrella of the Central

Aircraft Manufacturing Company (CAMCO), Aldworth toured military bases

across the United States to recruit pilots. He interviewed Marines at

Quantico, Navy personnel at Norfolk and San Diego, and Army personnel at

McDill, March, Mitchel, Langley, Hamilton, Eglin, Craig, Maxwell,

Barksdale and Randolph fields. Many pilots had to be interviewed at his

bedside as Aldworth was forced to periodically return to hospital. Over

300 men volunteered to serve with the Flying Tigers.

“Dick Aldworth did a magnificent job,” said Chennault, “although he knew

at the time he took the assignment that his days were numbered.”

In June 1942, Colonel Aldworth returned to San Antonio with the Air

Service Command at Duncan Field. Before being appointed chief of the

maintenance division, he was a technical instructor, special projects

officer, and assistant to the commanding general.

On September 1, 1943, Aldworth’s health dramatically deteriorated. On

September 17, paralyzed and in a sickroom banked with oxygen cylinders,

he gained just enough strength to permit his oxygen tent to be pushed

back, and General Gerald C. Brant awarded Colonel Aldworth the Legion of

Merit for meritorious service in recruiting personnel for the Flying

Tigers. Dick Aldworth died the following day, aged 45.

His Legion of Merit citation reads:

"Richard T. Aldworth, colonel (then first lieutenant, retired), air

corps, United States Army. For exceptionally meritorious conduct in the

performance of outstanding services from April 1941, to December 1941.

Col. Aldworth left the Walter Reed General Hospital in 1941 to undertake

the difficult assignment of selecting competent personnel for the

American Volunteer Group in China (more widely known as the 'Flying

Tigers').

"Despite countless rebuffs and at great detriment to his own health he

utilized his extensive background of service in the army air corps to

carry this arduous task through to a highly successful conclusion.

Activated by the highest patriotic motives, his steadfast devotion to

the cause of a friendly foreign nation proved indirectly of great

benefit to his own country. Col. Aldworth's accomplishments in the

furtherance of the war effort of the United Nations reflect the highest

credit upon himself and the army air forces."

“The death of Col. Richard "Dick" Aldworth,” wrote Harold Scherwitz,

Sports Editor of the San Antonio Light, “touched a responsive note in

the ranks of veteran San Antonio sports followers as the passing of few

men could do. For Aldworth was a sort of Dick Merriwell of local

athletics in the days just preceding World War I.”

George Tucker, who played infield on the Knights of Columbus team for

which Aldworth achieved much of his local fame, called him "one of the

finest, cleanest athletes who ever lived,” and another former teammate

said, “I never saw a better sportsman, a cleaner liver or a better

competitor. He was a remarkable fellow."

Funeral services were held on September 21, 1943, at Kelly Field Chapel

No. 2, by Chaplain Edward Burns, with internment at Fort Sam Houston

National Cemetery. He was survived by his widow, Estelle, and a

daughter, Agness.

|

Year |

Team |

League |

Class |

G |

IP |

ER |

BB |

SO |

W |

L |

ERA |

|

1916 |

New Haven |

Eastern |

B |

9 |

64 |

- |

43 |

- |

4 | 4 |

- |

Dick Aldworth in his days with the San Antonio Knights of Columbus team

Colonel Aldworth being presented with the Legion of Merit the day before

he died

Dick Aldworth's grave at Fort Sam Houston National Cemetery, San

Antonio, Texas

Thanks to Davis O. Barker for "discovering" Dick Aldworth. Thanks to Steve Boren for helping with medical information relating to Dick Aldworth's death.

Date Added November 11, 2016. Updated October 26, 2019

Baseball's Greatest Sacrifice is associated with Baseball Almanac

Baseball's Greatest Sacrifice is proud to be sponsored by